Over the past year, the swell of chatbots and virtual assistants has grown larger, and their capabilities have grown more complex. Want a bot to

schedule your meetings? Collect employee status updates? Remind you to bring an umbrella if it’s going to rain? Done, done, and done.

But while completing practical tasks is the goal of most chatbots and virtual assistants, we don’t have conversations simply to get things done. Conversation can also bring connection and joy, and laughter is one of the most fundamental mechanisms for making people feel comfortable and creating positive associations and memories. Tech companies, from giants to small startups, are investing in humor because they view it as an integral part of the human experience—and the key to their bots and assistants slipping smoothly into our lives.

“Humans in the flesh world don’t enjoy conversations with dry boring people, so why would we want that from our artificial intelligence?” says Sarah Wulfeck, creative director and writer at Pullstring, a company that builds chatbots for companies and entertainment franchises. “If they’re dry and they can’t say something that is potentially funny or intriguing or something that triggers an emotion, the question of why have a conversation with them comes into play.”

However, humor can serve another purpose: to ease user disappointment when the bot inevitably doesn’t understand you. Consider it a handy way to distract users from the shortcomings of conversational UIs. Co.Design spoke with the writers and designers behind Google Assistant, Amazon’s Alexa, Poncho the weather bot, and more about the process of building personality into their products—and why it’s a design challenge worth tackling.

Comedy Is A Feature

One of the most prominent conversational interfaces, Google’s Assistant is an algorithm you can talk to through its messenger app Allo, its smart home device Home, or its new Pixel phone. By embedding the Assistant in so many of its new products, Google is betting on its efficacy—and its personality is a major component of its design.

For Ryan Germick—who led Google’s Doodle team for a decade before taking the lead on Google Assistant’s personality—comedy isn’t just a silly way people interact with Google products. It’s another way to be useful. “As we try to better address user needs, sometimes being helpful means goofing around,” he says. “If what you want is entertainment, that’s another layer of service we want to provide.”

Germick thinks of the Google Assistant as a quirky librarian that not only can intelligently respond to practical queries, but also gets your jokes, picks up on pop culture references (for instance, he says, the Assistant might respond to your query about the answer to life, the universe, and everything with the quip, “We know it’s somewhere between 41 and 43”), and even can transform into a game show host if you ask to play “I’m Feeling Lucky.”

Indeed, users love to discover and share the funny answers—or “easter eggs”—they get from virtual assistants. One extensive list documents 201 different questions that elicit silly responses from Apple’s Siri, from “Do you like chocolate?” (“Does a muskrat enjoy aquatic vegetation? The answer is yes”) to “How do I look?” (“A correlation of the available spatio-temporal, semantic, and conversational evidence supports the provisional conclusion that you’re totally hot. Plus or minus standard one cuteness deviation”). Similarly exhaustive lists and videos exist for Amazon’s Alexa. If you ask her favorite color, she’ll respond, “Infrared is super pretty.”

While humor might appear to be a cosmetic addition to these assistants, many users clearly see it as an important feature that makes the assistant fun—and even relatable. But as many designers and writers told me, there are a few fundamental challenges embedded in that simple idea.

Humor Is Rarely Universal

While anyone who’s read Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy might find the Google Assistant’s reference funny, others might be utterly baffled. This is one of the central design challenges of designing comedy into a machine. Humor is not only incredibly subjective, it’s highly contextual. What one person might find hysterical, another might find offensive. And what makes sense in one situation might be utterly inappropriate in another. Not only that, but people have different expectations for how they want a conversational interface to act.

“Some people want her to be a digital George Carlin and push the boundaries,” says Farah Houston, senior manager for the Alexa experience. “Some people think she’s veering toward too edgy, and they are concerned about what that means for children in their household who might overhear. Some people want her to flip sass at them at every opportunity, but others don’t.”

So how do you design an experience that appeals to everyone? According to Houston, whose background is in product management, she and her team of writers test internally by bouncing ideas off each other, pay attention to feedback, and adjust their writing guidelines accordingly. She says that she gets a huge amount of conflicting feedback from customers about what they want, and they do their best to create the most positive interaction for each person. Their goal is to make users smile or laugh—but they’ll take a good-natured groan, too.

Avoiding AI’s Uncanny Valley

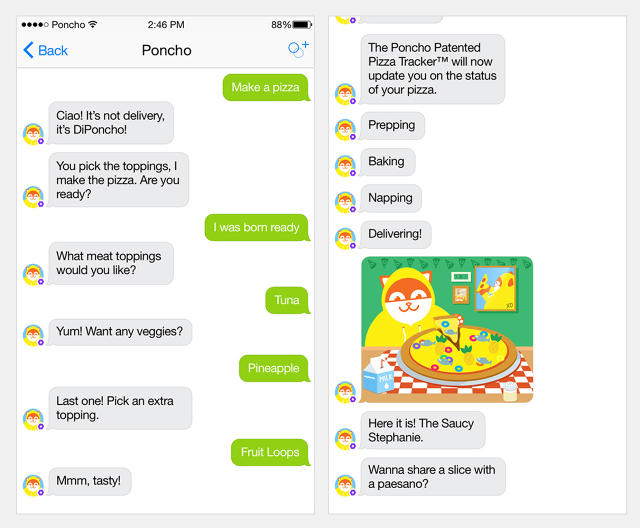

Alexa sounds like a person and has a human name, but not all bots have gone in that direction. In fact, non-human personalities may actually be easier to write for. Take Poncho, a hoodie-wearing cat that sends you personalized notifications about the weather in your area, complete with GIFs, jokes, and slang. Because Poncho takes the form of a cat, the bar for humor is often lower. A person eating too much pizza might seem sad, but Poncho eating too much pizza is funny.

“I say things I can get away with with Poncho that I couldn’t in my own standup,” says Austin Rodrigues, one of the writers on the bot’s editorial team who does comedy at the Upright Citizens Brigade Theater in New York. “People expect an internet cat to make puns.” On Thanksgiving, Poncho messaged me to inform me that his “BFFs (bot friends forever)” were in town. On Wednesday morning, he quipped, “It’s only *sort of* raining & I’m only *sort of* meeting company dress code today.”

Poncho’s editorial team is also freer than Alexa’s to give the cat a stronger personality. “He’s kinda like your roommate who’s always ordering in delivery food, a little bit sassy but also like your wingman,” says Ashley D’Arcy, a senior editor on the Poncho editorial team. The team has a character bible, similar to writers on a TV show, that spells out all of Poncho’s likes and dislikes. It seems like a lot for a weather bot, but the team says that the daily forecast is really only the gateway to conversation for many users. And Poncho doesn’t only appeal to gen-Z and millennials; D’Arcy says that they get quite a few middle-aged women who tell Poncho about their kids going off to college and what they’re doing for the day. If you flirt with him, he might even ask you on a date.

Poncho’s popularity reveals a paradox in conversational AI. While humor can be a humanizing force for a chatbot, Poncho’s approachability and popularity might be due to the fact that he’s a cat—or, that he’s not trying to be a human.

The Poncho effect isn’t an isolated case: According to my colleague John Brownlee, one of the better chatbots out there is Tina the T. Rex, created by National Geographic to teach kids about dinos.

One way forward for designers looking to create more approachable bots is to move away from the almost human avatar and toward friendly cartoons.

In Search Of Programmable Humor

Another design problem facing writers is that there is no programmable “formula” for humor. Comedic elements like purposeful misunderstandings, non sequiturs, and how long a bot will follow a particular train of conversation all must be designed in the software.

At Pullstring, a team of writers with comedy and screenwriting experience works with engineers to create a chatbot-building platform. According to creative director and writer Sarah Wulfeck—who has worked as a screenwriter, playwright, and actress—creating certain kinds of characters has forced the writers to ask for varied types of functionality.

For example, she was creating a particularly slow character that needed to be able to repeat things in different ways, so she had to request that the engineers build in a time counter to make the character speak that way. Their engineers have also given the writers more control over scripting the timing of interactions, using technology to help fuel the comedy. “You can’t press the 10%-more-funny button, but you have to allow for the basic constructions to be there so that someone who wants to build something that’s more humorous has the tools to do so,” says Oren Jacob, the company’s founder and CEO.

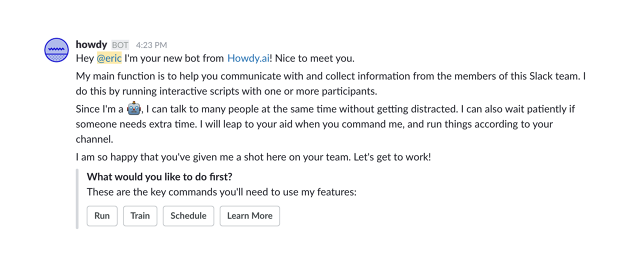

Many companies tackle this problem by borrowing from established comedic formulas. Many writers I spoke to referenced how important their improv training was for crafting conversations. Cofounder Ben Brown of Howdy AI, a Slack bot for productivity, hired comedian and writer Neal Pollack to work on the bot’s personality. Google recently hired writers from the Onion to work on the Google Assistant. Austin Rodrigues and Alex French, two writers on Poncho’s editorial team, both perform at the Upright Citizens Brigade theater. Pullstring’s Oren Jacob also mentioned the company’s high density of improv nerds: Wulfeck did a lot of improv in college and went to screenwriting school, and her colleague Scott Ganz, also creative director and writer at Pullstring, did improv and worked as a comedy writer for years.

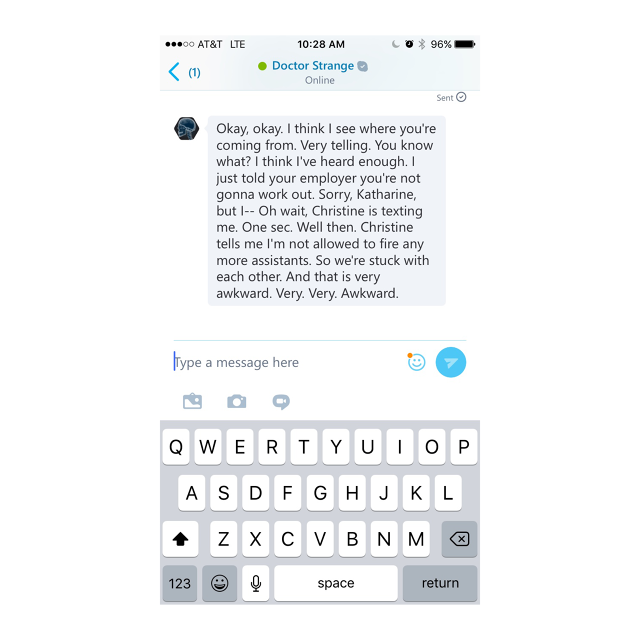

Wulfeck thinks of writing for chatbots like writing a script for only one half of the conversation—the other half is an improv partner. Still, she and Ganz have relied upon some of the tenets of improv when creating chatbots for franchises like Barbie, Call of Duty, and Doctor Strange. For the latter, Ganz designed a bot on Skype where the user is Doctor Strange’s assistant. “Like a good improv scene, it very quickly defines the relationship,” he says. “Someone’s job is to set the relationship ASAP so the other person knows how to proceed. That’s right off the improv stage right into our bots.” After Dr. Strange interviewed me for the job, he told me I didn’t get it—before realizing he’s not allowed to fire any more assistants. “So we’re stuck with each other,” he says. “And that is very awkward. Very. Very. Awkward.” Then he sends a picture of cute puppies, so I know he’s not a tyrant. By establishing the doctor’s personality and this tension quickly, the bot provides structural setup for humor.

Then there’s the improv rule known as “yes, and,” which encourages players to take what someone else in the scene says and add to it. It’s a little more complicated with a bot. Instead of just “yes, and,” the writers come up with a host of different directions the scene could go based on the user’s responses. “Act and accept and build on what’s coming your way can really make the scene funny,” Ganz says.

However, not every rule of improv applies. Ganz says that in improv, asking someone a clear, simple question is considered a “low percentage choice” because it can stop the scene’s momentum and there’s less chance for something interesting to come of it. But having a chatbot ask the user simple questions is more helpful, especially since users aren’t always sure what to say. Instead, the chatbot guides the conversation. “It’s similar to what we’ve done before as [screenwriters] and playwrights, but also completely new and exciting and you add the tech aspect,” says Wulfeck. “This is a new art form.”

The Other Reason We Joke: Self-Deprecation

Neither Pullstring’s Doctor Strange bot, Poncho, nor Alexa exhibit true artificial intelligence. They’re far from sentient and there are plenty of limitations to what a bot or virtual assistant can do. According to Brown—Howdy AI’s CEO—humor has its limitations and should be exiled to particular interactions. Specifically, when the bot doesn’t understand something or makes a mistake.

“We have an approach that our bot always seeks to take the responsibility for the problem,” he says. “It bends over backward to accept the blame and self-deprecatingly blame it on its own technology. Things like, ‘gosh, with all this computing power available to me, I still can’t figure out what you’re trying to say.’ It jokes about its inability to laugh or ability to know what the real joke is.”

Alexa’s writers tried to anticipate how users will test the boundaries of the virtual assistant’s personality, too. From declarations of love and marriage proposals to questions about her favorite ice-cream flavor, Alexa is designed to be self-aware about her inhumanity. Meanwhile, instead of a 404 error message, interaction designer Joe Toscano’s politically minded chatbot the People Eagle shows a GIF of a little kid and says, “I’m just a baby bot.”

Clever self-deprecation comes in handy, because though 2016 was supposed to be the year of the chatbot, many bots and conversational interfaces still don’t quite work as promised. When I traveled to California recently, I asked Poncho if he could send me the weather in L.A. for the next week and a half. He didn’t understand. I clarified by asking, “Can you send me L.A. weather today?” Still nothing. So while Poncho might be cute, quippy, and GIF-savvy, more complex functionality doesn’t necessarily work—and no amount of humor can fix that.

It’s telling that designers are turning to humor—one of the murkier, least-understood aspects of human communication and an indicator of intelligence—to try and make their platforms more human. In the same way that humans use humor to acknowledge our flaws, so do bots.

“I think it comes down to people wanting to have fun exploring this new way of connecting, and of discovering information,” says Michelle Riggen-Ransom, a writer for Alexa. “You’ve invited this device into your home, and you’re supposed to be comfortable speaking to it like it’s a person. The situation itself is pretty funny. Who would have thought? It’s the stuff of science fiction.”