What happens to a company when a visionary CEO is gone? Most often, innovation dies and the company coasts for years on momentum and its brand. Rarely does it regain its former glory.

Here’s why.

Microsoft entered the 21st century as the dominant software provider for anyone who interacted with a computing device. 16 years later, it’s just another software company.

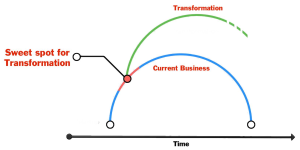

After running Microsoft for 25 years, Bill Gates handed the reins of CEO to Steve Ballmer in January 2000. Ballmer went on to run Microsoft for the next 14 years. If you think the job of a CEO is to increase sales, then Ballmer did a spectacular job. He tripled Microsoft’s sales to $78 billion, and profits more than doubled from $9 billion to $22 billion. The launch of the Xbox and Kinect, and the acquisitions of Skype and Yammer happened on his shift. If the Microsoft board was managing for quarter to quarter or even year to year revenue growth, Ballmer was as good as it gets as a CEO. But if the purpose of the company is long-term survival, then you could make a much better argument that he was a failure as a CEO, as he optimized short-term gains by squandering long-term opportunities.

How to Miss the Boat – Five Times

Despite Microsoft’s remarkable financial performance, Ballmer failed to understand and execute on the five most important technology trends of the 21st century: in search – losing to Google; in smartphones – losing to Apple; in mobile operating systems – losing to Google/Apple; in media – losing to Apple/Netflix; and in the cloud – losing to Amazon. Microsoft left the 20th century owning over 95 percent of the operating systems that ran on computers (almost all on desktops). Fifteen years and 2 billion smartphones shipped in the 21st century and Microsoft’s mobile OS share is 1 percent. These misses weren’t in some tangential markets – search, mobile, and the cloud were directly where Microsoft users were heading. Yet a very smart CEO missed all of these. Why?

Execution and Organization of Core Businesses

It wasn’t that Microsoft didn’t have smart engineers working on search, media, mobile, and cloud. They had lots of these projects. The problem was that Ballmer organized the company around execution of its current strengths – Windows and Office businesses. Projects not directly related to those activities never got serious management attention and/or resources.

For Microsoft to have tackled the areas it missed – cloud, music, mobile, apps – would have required an organizational transformation to a services company. Services (cloud, ads, music) have a very different business model. They are hard to do in a company that excels at products.

Ballmer and Microsoft failed because the CEO was a world-class executor (a Harvard grad and world-class salesman) of an existing business model trying to manage in a world of increasing change and disruption. Microsoft executed its 20th-century business model extremely well, but it missed the new and more important ones. The result? Great short-term gains, but less compelling long-term prospects.

In 2014, Microsoft finally announced that Ballmer would retire, and in early 2014, Satya Nadella took charge. Nadella got Microsoft organized around mobile and the cloud (Azure), freed the Office and Azure teams from Windows, killed the phone business and got a major release of Windows out without the usual trauma. And he is moving the company into augmented reality and conversational AI. While Microsoft will likely never regain the market dominance it had in the 20th century, (its business model continues to be extremely profitable), Nadella likely saved the company from irrelevance.

What’s Missing?

Visionary CEOs are not “just” great at assuring world-class execution of a tested and successful business model, they are also world-class innovators. Visionary CEOs are product and business model centric and extremely customer focused.

The best are agile and know how to pivot – make a substantive change to the business model while or before their market has shifted. The very best of them shape markets – they know how to create new markets by seeing opportunities before anyone else. They remain entrepreneurs.

One of the best examples of a visionary CEO is Steve Jobs, who transformed Apple from a niche computer company into the most profitable company in the world. Between 2001 and 2008, Jobs reinvented the company three times. Each transformation – from a new computer distribution channel, Apple Stores, to disrupting the music business with iPod and iTunes in 2001 to the iPhone in 2007 and the App store in 2008 – drove revenues and profits to new heights.

These were not just product transitions but radical business model transitions – new channels, new customers, and new markets – and new emphasis on different parts of the organization (design became more important than the hardware itself, and new executives became more important than the current ones).

Visionary CEOs don’t need someone else to demo the company’s key products for them. They deeply understand products, and they have their own coherent and consistent vision of where the industry/business models and customers are today and where they need to take the company. They know who their customers are because they spend time talking to them. They use strategy committees and the executive staff for advice, but none of these CEOs pivot by committee.

Why Tim Cook Is the New Steve Ballmer

And that brings us to Apple, Tim Cook, and the Apple board.

One of the strengths of successful visionary and charismatic CEOs is that they build an executive staff of world-class operating executives (and they unconsciously force out any world-class innovators from their direct reports). The problem is in a company driven by a visionary CEO, there is only one visionary. This type of CEO surrounds himself/herself with extremely competent executors but not disruptive innovators. While Steve Jobs ran Apple, he drove the vision but put strong operating execs in each domain – hardware, software, product design, supply chain, manufacturing – who translated his vision and impatience into plans, process, and procedures.

When visionary founders depart (death, firing, etc.), the operating executives who reported to them believe it’s their turn to run the company (often with the blessing of the ex CEO). At Microsoft, Bill Gates anointed Steve Ballmer, and at Apple, Steve Jobs made it clear that Tim Cook was to be his successor.

When visionary founders depart (death, firing, etc.), the operating executives who reported to them believe it’s their turn to run the company (often with the blessing of the ex CEO). At Microsoft, Bill Gates anointed Steve Ballmer, and at Apple, Steve Jobs made it clear that Tim Cook was to be his successor.

Once in charge, one of the first things these operations/execution CEOs do is to get rid of the chaos and turbulence in the organization. Execution CEOs value stability, process, and repeatable execution. On one hand, that’s great for predictability, but it often starts a creative death spiral – creative people start to leave, and other executors (without the innovation talent of the old leader) are put into more senior roles. The company hires more process people, which in turn forces out the remaining creative talent. This culture shift ripples down from the top, and what once felt like a company on a mission to change the world now feels like another job.

As process oriented as the new CEOs are, you get the sense that one of the things they don’t love and aren’t driving are the products (go look at the Apple Watch announcements and see who demos the product).

Cook has now run Apple for five years, long enough for this to be his company rather than Steve Jobs’. The parallel between Gates and Ballmer and Jobs and Cook is eerie. Apple under Cook has doubled its revenues to $200 billion while doubling profit and tripling the amount of cash it has in the bank (now a quarter of trillion dollars). The iPhone continues its annual upgrades of incremental improvements. Yet in five years, the only new thing that managed to get out the door is the Apple Watch. With 115,000 employees, Apple can barely get annual updates out for its laptops and desktop computers.

But the world is about to disrupt Apple in the same way it disrupted Microsoft under Ballmer. Apple brilliantly mastered User Interface and product design to power the iPhone to dominance. But Google and Amazon are betting that the next of wave of computing products will be AI-directed services – machine intelligence driving apps and hardware. Think of Amazon Alexa, Google Home, and Google Assistant directed by voice recognition that’s powered by smart, conversational artificial intelligence – and most of these will be a new class of device scattered around your house, not just on your phone. It’s possible that betting on the phone as the platform for conversational AI may not be the winning hand.

It’s not that Apple doesn’t have exciting things in conversational AI going on in its labs. Heck, Siri was actually first. Apple also has autonomous car projects, AI-based speakers, augmented and virtual reality, etc in its labs. The problem is that a supply chain CEO who lacks a passion for products and has yet to articulate a personal vision of where Apple will go is ill equipped to make the right organizational, business model, and product bets to bring those to market.

Four Challenges for the Board of Directors

The dilemma facing the boards at Microsoft, Apple, or any board of directors on the departure of an innovative CEO is strategic: Do we still want to be a innovative, risk taking company? Or should we now focus on execution of our core business, reduce our risky bets, and maximize shareholder return.

Tactically, that question results in asking: Do you search for another innovator from outside, promote one of the executors, or go deeper down the organization to find an innovator?

Herein lie four challenges. Jobs and Gates (and the 20th century’s other creative icon, Walt Disney) shared the same blind spot: They suggested execution executives as their successors. They confused world-class execution with the passion for product and customers and market insight. Gates saw no difference between him and Ballmer. Yet history has shown us that, for long-term survival in markets that change rapidly, there definitely is a difference in these types of CEO.

The second conundrum is that if the board decides that the company needs another innovator at the helm, you can almost guarantee that the best executor – the number 2 and/or 3 vice president in the company – will leave, feeling that they deserved the job. Now the board is faced with not only having lost its CEO but potentially the best of the executive staff.

The third challenge is that many innovative/visionary CEOs have become part of the company’s brand. Jobs, Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, Jeff Immelt, Elon Musk, Mark Benioff, Larry Ellison. This isn’t a new phenomenon, think of 20th-century icons like Walt Disney, Edward Land at Polaroid, Henry Ford, Lee Iacocca at Chrysler, Jack Welch at GE, and Alfred Sloan at GM. But they’re not only an external face to the company, they are often the touchstone for internal decision-making. Years after a visionary CEO is gone, companies are still asking “What would Walt Disney/Steve Jobs/Henry Ford have done?” rather than figuring out what they should now be doing in the changing market.

Finally, the fourth conundrum is that, as companies grow larger and management falls prey to the fallacy that it only exists to maximize shareholder short-term return on investment, companies become risk averse. Large companies and their boards live in fear of losing what they spent years gaining (customers, market share, revenue, profits.) This may work in stable markets and technologies. But today very few of those remain.

In the 21st Century an Execution CEO as a Successor Increasingly May be The Wrong Choice

In a startup, the board of directors realizes that risk is the nature of new ventures and innovation is why they exist. On day one there are no customers to lose, no revenue and profits to decline. Instead, there is everything to gain. In contrast, large companies are often risk-averse engines – they are executing a repeatable and scalable business model that spins out the short-term dividends, revenue, and profits that the stock market rewards. And an increasing share price becomes the reason for existing. The irony is that in the 21st century, the tighter you hold onto your current product/markets, the likelier you are to be disrupted. (As articulated in the classic Clayton Christensen book The Innovators Dilemma, in industries with rapid technology or market shifts, disruption cannot be ignored.)

Increasingly, a hands-on product/customer, and business model-centric CEO with an entrepreneurial vision of the future may be the difference between market dominance and Chapter 11. In these industries, disruption will create opportunities that force “bet the company” decisions about product direction, markets, pricing, supply chain, operations, and the reorganization necessary to execute a new business model. At the end of the day, CEOs who survive embrace innovation, communicate a new vision, and build management to execute the vision.

Lessons Learned

- Innovation CEOs are almost always replaced by one of their execution VPs

- If they have inherited a powerful business model, this often results in gains in revenue and profits that can continue for years

- However, as soon the market, business model, or technology shift, these execution CEOs are ill-equipped to deal with the change. The result is a company obsoleted by more agile innovators and left to live off momentum in its twilight years

[This story originally ran on the author’s blog.]

Steve Blank is a retired serial entrepreneur-turned-educator who has changed how startups are built and how entrepreneurship is taught. He created the Customer Development methodology that launched the lean startup movement, and wrote about the process in his first book, The Four Steps to the Epiphany. His second book, The Startup Owner’s Manual, is a step-by-step guide to building a successful company. Blank teaches the Customer Development methodology in his Lean LaunchPad classes at Stanford University, U.C. Berkeley, Columbia University, UCSF, NYU, the National Science Foundation and the I-Corps @NIH. He writes regularly about entrepreneurship at www.steveblank.com.