MADISON, Wis. — In early April when UL (Underwriters Lab) launched its new cybersecurity standard, dubbed UL 2900, for the testing and certification of connected devices, reactions from the Internet of Things (IoT) market were split.

On one hand, cybersecurity experts surmised that UL was in over its head.

After all, the safety organization, founded 122 years ago, was originally built on safety standards for the public adoption of electricity. People worried about safety of electrical wiring.

However, plenty of people thought it high time for the well-respected organization — a guardian of safety standards for a host of products — to weigh in on cybersecurity issues for emerging connected devices. UL proponents are hoping it can bring “adult supervision” to a deeply fragmented Internet of Things (IoT) market – where too many connected devices are designed with too little security.

Three months after the UL announcement, EE Times talked to some IoT technologists. How is UL 2900 being viewed and accepted? We also asked more about the UL 2900 standard from Ken Modeste, principal engineer of security and global communications at UL.

Despite lagging public perceptions and a discrepancy between UL’s cybersecurity goals and what UL offers today, UL intends to play an important role in the IoT community. The industry should benefit from “scientific, repeatable and reproducible criteria” for assuring quality of their products – whether applied to software, chips, components or end systems, as UL’s Modeste pointed out.

A big unknown, however, is how UL’s Cyber Assurance Program will define commonality among cybersecurity practices, at a time when device vendors are already burdened with myriad compliance requirements set forth by each vertical IoT segment.

Market traction

Right now, the UL 2900 standard is still in early days.

Daniel Cooley, senior vice president and general manager of IoT products at Silicon Labs, told us that he’s aware of the UL 2900 standard but “I haven’t dug into it yet.” His customers so far haven’t asked for UL2900 certification on Silicon Labs’ IoT processors, he explained.

However, Cooley observed, “The pendulum is swinging back.” Some customers are now “going hardcore” with security, he said, as they look for ways to build into their specs things such as encryption, cipher core and secure debugging, while others ask for code review.

Sami Nassar, vice president of cyber security solutions at NXP Semiconductors, told EE Times, “As a technology vendor, we find getting a third-party certification is always a good thing. It helps to differentiate good products from bad.”

Next page: One-on-one with UL

Security by design

But Nassar provided a few cautions. Whether a connected vehicle or a smart home solution such as that of Apple’s HomeKit or Google’s Weave, “Each vertical [IoT] segment already has its own set of compliance requirements for interoperability and security.”

He stressed, “We want to encourage UL to get into security certifications.” But it won’t be easy for the group to “uniformalize” a cybersecurity standard to cut across the industries, he added. UL 2900, for now, might be useful only for products in industry pockets where compliance requirements don’t exist, he suspected.

UL relies on a publicly-available government vulnerability database – put together by NIST – to identify risks. UL helps IoT designers build secure products by avoiding the use of software or components with known vulnerabilities.

However, NXP’s Nassar stressed, “It’s more important to build security in from the get-go.” Stressing “security by design,” he added, “If you have to improve your security after a new vulnerability is exposed, you are already falling behind.”

Making any security standards genuinely effective and trusted takes time. UL 2900 is no exception.

Take the Common Criteria, for example, Nassar said. Its genesis lies in efforts that began in the 1980s, initiated by credit card companies. Its stringent security requirements became a standard to protect consumers’ secret data in ICs, explained Nassar.

It now offers a framework in which computer system users can specify their security requirements through Protection Profiles. “Some IoT vendors are aware of Common Criteria, and I know of a door-lock company who asked for an IC that’s Common Criteria certified,” Nassar said.

Building a security standard doesn’t always have to start from scratch, he noted. “You can build on what’s already proven, take it to new industries and spread it.”

One-on-one with UL

EE Times spent some time with UL’s Ken Modeste so that we get to know UL and more about UL 2900. In the following pages, we summarize our Q &A with Modeste.

EE Times: Who will benefit from UL 2900?

UL: We have three categories of people in mind. First, there are manufacturers and designers of systems. Second, those in supply chains and owners of assets who want to know where critical components and software came from. Third, there are those working in the security department of organizations.

EE Times: Why do they need it?

UL: Asset owners – like hospitals, gas/oil refineries, and large organization that use HVAC or IT equipment, for example – approached UL. They asked us if they could be assured that they aren’t procuring products that come with known cybersecurity vulnerabilities.

EE Times: I don’t want to sound disrespectful, but some in the industry question what an old-line safety outfit like UL actually knows about cybersecurity.

Next page: What do you test?

UL: We’ve been in the security field for over 20 years. We developed FIPS 140 (The Federal Information Processing Standards are U.S. government computer security standards that specify requirements for cryptography modules). We’ve also worked on Payment Card Industry (PCI) standards and Common Criteria. We’ve been in the cybersecurity space for at least the last 10 years.

EE Times: That may be so, but UL’s name doesn’t usually pop up when cybersecurity people talk about firewalls, intrusion systems or anti-virus products.

UL: Yes, there are well-known players in the cybersecurity space. But a big part of cybersecurity requirements involves testing, assessing and consulting services. UL’s technical experts are well informed and versed in the topics, and we’ve been offering valuable services. We identify security risks and help product manufacturers build in their systems certain capabilities that can address such risks.

EE Times: How long have you been developing UL Cyber Assurance Program (CAP)?

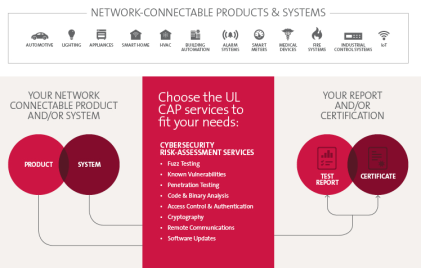

UL: Over the last three to four years. We saw challenges emerging as security issues started to crop up in the field outside the traditional IT space. Risks are spreading out into HVAC, automotive, lighting, factory automation and medical fields.

The U.S. Federal government wanted a trusted third party like UL to develop the testing standards as part of a voluntary program. They wanted us to work with industry officials and academics.

In fact, President Obama’s Cybersecurity National Action Plan asked UL to work with the Department of Homeland Security to develop CAP. More specifically, UL was tasked to develop testable security criteria, through which UL can test, validate, authenticate and certify networked devices.

What do you test?

EE Times: What do you exactly test?

UL: Software used within products – ranging from chips to components and systems. We look at existing vulnerabilities, defects and patches known to third-party vendors. We test to discover coding errors and security loopholes in software, operating systems or networks.

We see how a system accesses remote devices and do software updates. We offer structured penetration testing regimen, and see if we can plug those holes. We define flaws and weaknesses and provide scientific repeatable and reproducible testing criteria.

EE Times: I see UL 2900-1 and 2900-2 standards. What are the differences?

UL: The UL 2900-1 covers all the requirements ranging from automotive components to washers/driers and lighting. The UL 2900-2 was developed to address additional specifications specific to certain segments – like medical and industrial control. For example, authentication is critical for many connected devices. But when a doctor has to use an urgent care infusion pump and he can’t remember the password, it sort of defeats the whole purpose.

Next page: Does UL cover automotive?

EE Times: My understanding is that UL CAP will rely on the NIST’s vulnerability database. Why that database?

UL: NIST has already built a public, free-to-use vulnerability database. It has identified and tracked vulnerability. It also lists flaws and patches, and identifies which version of software has a patch to address a specific security flaw.

Now, the expanded database – integrated with all additional vulnerabilities, which are constantly updated, enumerated worldwide, managed and funded by the Department of Homeland Security – is under the purview of Homeland Security. Asset owners can look at the repository of the new data, and get a patch for it when it’s needed.

Does UL 2900 cover automotive?

EE Times: What sort of product categories does this database cover?

UL: The database has a multitude of product lists, including desktop and mobile platforms.

EE Times: Does the database cover automotive? Does UL 2900 address automotive security?

UL: We cover automotive components but not vehicles.

EE Times: Why not? Isn’t the connected vehicle generally considered as an IoT device?

UL: When it comes to data related to automotive recalls and any other automobile-related vulnerability, a massive repository of such data belongs to the automotive industry. But UL 2900 may apply to certain software used in automotive components or semiconductors.

EE Times: What sort of traction have you already received for CAP? Can you name names or a number of entities that have signed onto the UL 2900 certification program?

UL: We currently have 100 products in the pipeline. The first cybersecurity certifications are expected to come in the third quarter of this year. Those in the certification process include systems used in critical infrastructure, medical device, healthcare system and automotive components.

EE Times: Some in the industry described UL’s CAP launch as ‘bringing adult supervision’ to IoT devices. Do you agree?

UL: (laugh) We would like to think our program enables IoT innovation.

EE Times: Clearly, you aren’t the only group looking at cybersecurity certification. What role do you see UL playing?

UL: When it comes to cybersecurity, there is no silver bullet. We need a layered approach. But we see ourselves joining the conversation and bringing our 120-year history to help organizations understand cybersecurity risks when they develop new features and new capabilities for their connected devices.

EE Times: I know earlier this year when UL announced the launch of the CAP, your organization was criticized for charging members to obtain UL 2900 documentation. What was the problem?

UL: I don’t think there were problems. We’ve been openly working with a number of government and industry stakeholders. They’ve seen the standard and contributed to the standard development. There is nothing new about charging the document. It’s in line with what organizations such as the IEEE or IEC does.

EE Times: Are you a for-profit company now?

UL: In 2012, UL transformed from a non-profit company into a for-profit corporation. We decided to make that change due to the way we report to the IRS on some of the businesses we do abroad. But our parent company remains a non-profit organization.

— Junko Yoshida, Chief International Correspondent, EE Times