MA student Alex Gamela took this image of the Telegraph newsroom during the first year of the MA

My MA in Online Journalism has a new name: the MA in Multiplatform and Mobile Journalism. It’s still a course all about finding, publishing and distributing journalism online. So why the name change?

Well, because what ‘online‘ means has changed.

For the last 18 months I’ve been talking to people across the industry, reflecting on the past 7 years of teaching the MA, and researching the forthcoming second edition of the Online Journalism Handbook. Here, then, are the key conclusions I arrived at, and how they informed the new course design:

1: Adapting to new platforms is a specific skill

In the last few years a significant change has taken place. Journalism is now increasingly ‘native’, playing to the strengths of multiple platforms rather than just using them as promotional ‘channels’. It went from web and social to chat, keeps remembering email, and in the near future will take in cars, the home and other connected devices too.

Since the very start of the original MA in Online Journalism it was always about more than just publishing to a website. Indeed, the first assignment that students were given involved exploring a specific platform other than a traditional CMS (examples have ranged from Instagram and Twitter to Apple News, Amazon Alexa, Snapchat, Facebook, YouTube, and even Google Wave)

The point wasn’t just becoming an expert in at least one platform, but developing a process for assessing any new platform and testing what we do on it. Part of that is being able to research best practice, speak to those working at the cutting edge, apply those practices in your own journalism, and use analytics tools effectively to measure the success against your own objectives.

Without those skills we risk chasing numbers of the sake of it, or trying to apply techniques from one platform onto another: a form of social media shovelware, if you like.

2: Multiplatform newsrooms take work

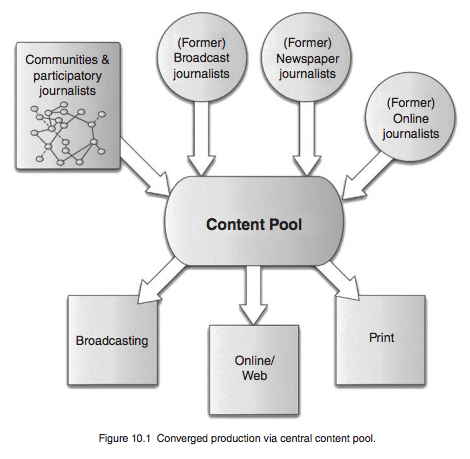

Converged newsroom image by Quandt and Singer

Single-media courses concerned with broadcast or print come with a certain collection of (sometimes outdated) assumptions about newsroom culture. But an online journalist doesn’t know what type of organisation they might be working in.

If the first sense of the term ‘multiplatform‘ is the way that we have to publish across multiple platforms online, the second sense of the term is the way that online journalists often work within broadcast or print organisations.

Anyone who has worked in a multiplatform organisation knows the challenges this throws up: how do you work together to ensure that stories are given the best treatment across TV and online, radio and web, or print and social? In what way are they web-first, or mobile-first?

This is as much a cultural challenge as a technical one, so I’ve been placing my students in a range of newsroom contexts — from TV-and-web and radio-and-web to online-only — to get them to think about how those contexts affect the dynamics of production, while exploring research on the realities of converged newsrooms.

This generation isn’t just defining the language of the medium (see below), but defining the spaces and routines in which journalism takes place. That requires thought and space.

3: Mobile-first is the starting point for all news now

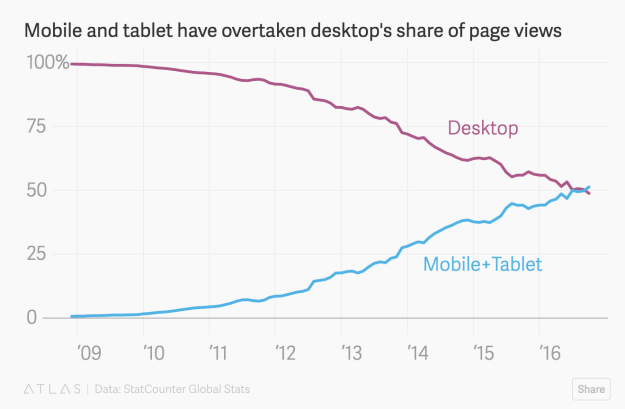

One of the biggest shifts in the last few years has been the rapid shift from the majority of users being on desktop, to the majority being on mobile.

This shift has happened in different ways in different places in different times. The Guardian and BBC noticed it happening at weekends in mid-2013, and within 12 months most newspaper and magazine publishers were saying that mobile was their main source of traffic. Another year on and some were reporting mobile traffic two or three times as high as desktop.

This year the picture has been further complicated by the rollout of Facebook Instant Articles, Google AMP’s surprising traffic, the prominence of Apple News in this September’s iOS update, and Google search announcing it would be splitting its index into mobile and desktop versions.

Broader trends to watch include the rise of socially-native bots, and voice-based user interfaces.

And mobile-first isn’t just about publishing: mobile-first newsgathering means journalists must be able to publish and broadcast from the places where news is happening. Understanding how to do this quickly and effectively — to make the right choices when under pressure, and have the technical ability to deliver, is a crucial part of journalism. Verification of information that is often rapidly shared in those contexts adds a further crucial dimension.

Both aspects of ‘mobile-first’ — publishing, and reporting — need to be front-and-centre in any online journalism course. So I’ve put it in the title.

4: Journalists need to learn about narrative, not just writing

In the pre-multiplatform era trainee journalists were taught how to write on one platform and in a limited number of formats that had existed for decades.

That approach, in the language of the web, “doesn’t scale”.

Once you move from one platform to dozens, and when new features and new platforms are added to the list every year, you need a different approach.

Students don’t just need to know how to ‘write for Twitter’, they need to know how to adapt when a new feature like Twitter Moments is launched, or a new chat platform like Snapchat emerges as a key player. And it is pointless only learning how to create studio programming when online audiences demonstrate a preference for different forms of video online.

My solution to that has been in part to adopt a narrative-based approach. Narrative principles can help you adapt to new platforms quickly and use them effectively. When looking at Snapchat, for example, you can apply principles of composition to vertical video, understand the importance of sound, and apply techniques involving sequence, movement, character and setting.

They also help you deal with data-driven stories which often need careful management not to get bogged down with numbers or charts, and to engage with an audience.

That narrative-based approach is now right at the front of the new course, with a dedicated module helping students to explore a whole range of storytelling forms from video and visual journalism to audio, data visualisation, GIFs, and interactivity. It also explores the ethical issues that storytelling techniques raise.

In a nutshell, we shouldn’t be teaching this generation merely how to write for different platforms; we should be helping them to invent the language of the web, because that’s what is happening.

5: Coding is both literacy and law

Coding runs throughout the course, both in production and in law.

For decades we have insisted that journalists learn about the structures of power that they report on (and find stories within), and the law that shapes how they report. It has seemed increasingly strange to me, then, that we should ask whether journalists should understand code.

Code is one of the most powerful structures we operate within as digital journalists. And code is a law that shapes how we report.

Needless to say, then, that students need to learn about source protection and information security alongside the legal, regulatory and ethical frameworks that shape those issues.

The next phase of online journalism

I’ve now been working in online journalism for two decades. I learned early on when designing teaching around technology that it was essential to design future-proofing and adaptability into any course. Courses should be platform-neutral by design: classes need to be flexible enough to respond to developments, and students given the space to anticipate the challenges they are likely to face when they re-enter the industry.

If anything the shift from the word ‘online’ to ‘multiplatform’ is an acknowledgement of that. We cannot know in advance whether those platforms will use the internet, the web that sits on top of it, or mesh networks that attempt to operate outside of it. It’s still online journalism, but acknowledging its fragmentation is the first step towards its next phase.