There’s a new gold rush in tech, related to voice assistance and a voice-first interface for everything we do at home, in the car and while out and about. What happens if the world’s best positioned, most profitable tech company fails to capitalize on it?

Apple introduced Siri back in 2011 as a key marketing feature of iPhone 4s and iOS 5. While much of the technology behind Siri was acquired by Apple, the company integrated specialized voice logic hardware support to make Siri’s voice recognition work better.

Voice-first gets mocked by Google, Microsoft

Executives from Google and Microsoft initially went on record as stating that Apple’s voice-first Siri was totally the wrong thing to be doing. These weren’t just upper-level executives isolated from mobile operations. Andy Rubin, Google’s lead developer of Android, insisted that he didn’t “believe that your phone should be an assistant” like Siri

Andy Rubin, Google’s lead developer of Android, insisted that he didn’t “believe that your phone should be an assistant” like Siri.

Microsoft’s Andy Lees, who was managing Windows Phone 7 development, was also quick to say he didn’t think Siri was “super useful,” indicating his company would avoid having its users speak commands to their phones in public.

However, Apple continued focused on Siri as a way to drive iPhone demand. That strategy focused on making Siri both useful and entertaining, and targeted broad language support. Initially supporting American, Australian and UK English, French and German, Apple announced new support for Siri in Japanese, Chinese, Korean, Italian and Spanish within its first year.

Siri makes Apple money

Siri exclusivity on iPhone 4s drove sales by helping Apple to stand out in the increasingly competitive market for smartphones. Rivals noted this. In 2012, Google Now got introduced as the voice assistant for Android 4.1. However, while Apple’s iOS 6 began bringing Siri support to every new device Apple sold, Android 4.1 was limited to a slow, incremental rollout over just the premium fraction of the Android installed base.

In early 2013, Google Now was ported to iOS and the company’s Chrome PC browser, two reminders of where Google actually makes its money.

Meanwhile, Apple introduced a new UI for Siri in iOS 7 and announced CarPlay (initially branded “iOS in the Car”) as a way to make Siri useful as an extension of the company’s initial Eyes-Free voice-first Siri interface for automotive.

Google subsequently copied Apple’s implementation of CarPlay a year later, but as with Google Now, Android Auto didn’t work across all Android phones; it was only compatible in certain ways with portions of the mostly premium fragment of Android’s installed base.

In contrast, just as Siri drew attention to iPhone and iPad, Siri Eyes-Free and CarPlay began attracting considerable attention among car buyers who wanted to leverage their existing iPhone to access entertainment and features such as Maps for navigation (an otherwise very expensive option on new cars).

While CarPlay brought iPhone’s Siri to driving, Apple further expanded Siri use cases to wearables with Apple Watch in 2014 and to the living room with the 2015 Apple TV with Siri Remote. That same year, Apple introduced the always-listening “Hey Siri” feature to iPhone 6s models.

Last year, Apple further expanded Siri to macOS Sierra and then made Siri the primary interface for AirPods, featuring beamforming microphones. Siri is now a prominent feature appearing across Apple’s entire hardware lineup.

How big are Siri sales? In fiscal 2016, Apple sold over 211 million iPhones, over 45 million iPads, over 18 million Macs and $11 billion worth of Other products, including Apple TV and Apple Watch. A total of $215.6 billion worth of products and services, virtually all of which incorporate voice-first functionality through Siri.

For everyone thinking Apple isn’t getting usage data to make Siri smarter, Siri is by far the most used voice assistant than any out there.

—Ben Bajarin (@BenBajarin) June 3, 2016

Siri rivals get massive airplay, generate little money

Apple’s Siri critics swiftly tried to catch up. In addition to Google Now, Microsoft introduced its own Cortana assistant tied to Windows 10 in 2015, while Amazon released its own Alexa service connected to its Echo always-on home appliance at the end of 2014.

All three voice-first rivals to Siri offer significant advantages. Alexa, Cortana and Google Now (along with the company’s latest machine learning assistant features) all offer to do some things Siri can’t. Google introduced always-listening mobile hardware first, and Amazon was first to market with a home appliance that connected to a variety of outside services.

However, there’s little evidence that Siri’s rival voice services have measurably helped to generate significant revenues (relative to Siri). While Google’s flagship Pixel phones promoted intelligent voice assistance features as a strong differentiation from other Android phones, this didn’t have an apparent impact on Pixel sales, which drowned in a sea of cheap commodity droid shipments.

The most enthusiastic of Pixel estimates, from Morgan Stanley’s Brian Nowak, suggested that Google’s Pixel phones might sell 3 million units in its first year, generating $2 billion in revenues, and could double in 2017 to achieve 5-6 million units and $3.8 billion in revenues. If achieved, that’s still barely 2 percent of Apple’s iPhone business. That’s around half the revenue of Apple’s first year of Watch sales.

Cortana is having no success in rescuing Microsoft’s stagnant Windows 10 PC market, and did nothing to make Windows Phones or Tablets relevant again. Microsoft’s Surface business, carved from backs of its Windows OEM partners, similarly generates less than $1 billion every quarter. That’s also less than Apple Watch, but far less than the more than $50 billion in hardware Apple sells in the average quarter.

What about Amazon? While the company avoids reporting sales numbers, Consumer Intelligence Research Partners stated in November that Amazon only sold 2 million Echo units in the first nine months of 2016. Consumer Intelligence Research Partners stated that Amazon only sold 2 million Echo units in the first nine months of 2016

Amazon likes to talk about rates of growth, but at its current scale it would need a lifetime of years to rival Apple’s hardware. Even at full retail price, that means Echo revenues for Amazon were at most $360 million across the first three quarters of the year.

Siri rivals laughing all the way to the blank

Siri obviously isn’t the only reason Apple has $215 billion in revenues every year. However, the narrative that Apple is falling behind in voice-first services because its rivals have some superior features (like Google’s conversational processing) or product offerings (like Amazon’s Echo speaker appliance) is massively delusional.

I’m not making up a straw man narrative. Writing for Time, Lisa Eadicicco announced “Amazon Is Already Winning the Next Big Arms Race in Tech!”

Time doesn’t call this an editorial

Clearly this idea is not based in economic reality, as Eadicicco admitted early on, writing: “the most convincing evidence of the Seattle-based giant’s advantage? Alexa, Amazon’s voice assistant, is dominating this year’s CES.”

Previous CES events have provided “convincing evidence” that consumers want curved smartphones, 3D TVs, smartbands and non-Apple smartwatches, and mobile video game consoles based on Nvidia’s Tegra K1. To extrapolate success from CES is simply asinine.

While a variety of appliance makers have licensed Amazon’s Alexa voice assistant at CES, the same sort of thing happened among netbook makers licensing Windows, TV box makers licensing Google TV, smartwatches licensing Android Wear, and so on, ad nauseam.

Apple’s Siri is not a Blackberry

The idea that Apple could be Blackberried out of existence by a new, superior voice-first UI technology is a delicious notion to Apple’s rivals, who have no other hope of ever catching up to the company’s massive scale of hardware sales. Even Apple’s “beleaguered” iPad business is larger and more profitable than Amazon’s Alexa, Microsoft’s Surface and Google’s Pixel businesses combined, and then multiplied by ten. Even Apple’s “beleaguered” iPad business is larger and more profitable than Amazon’s Alexa, Microsoft’s Surface and Google’s Pixel businesses combined, and then multiplied by ten

However, Blackberry didn’t lose its very profitable smartphone business to a hardware neophyte that had stumbled upon the iPhone’s multitouch user interface as part of a skunkworks effort. Apple was already a massive consumer hardware maker before it introduced iPhone, thanks in large part to billions of dollars in revenue from tens of millions of iPod sales.

After iPhone shipped, Blackberry did attempt to leverage its own profits and resources to develop a similarly high powered, multitouch phone. However, its Blackberry Storm wasn’t a good product and offered nothing new that iOS didn’t. Blackberry’s profits cratered as buyers decisively moved from keypad phones to iPhones, which offered to do far more than a messaging-centered Blackberry could.

There is currently zero evidence that Apple’s customers are similarly shifting from Siri to other voice-based competition in a way that actually hurts Apple’s profitability. The popularity of Echo among Amazon customers offers some indication that there could someday be real profits connected to a voice-based home appliance in the future, but Apple is also aware of this and better prepared to defend itself than Blackberry was.

Consider Microsoft’s defense against the web

For a better example of how economic power influences the tides in technology development, consider Microsoft in the mid 1990s. Like today’s Apple and iOS, Microsoft had established Windows as a solid software development platform governing the primary, mainstream embodiment of personal computers, evident in its revenues.

Microsoft’s control over PCs and apps with Windows was initially threatened by Netscape, Sun and their combined potential platform of Java apps running within a web browser. Many rivals of Microsoft predicted that Windows was on borrowed time and would not recover from an erosion of platform strength caused by a shift to web apps, particularly in the enterprise.

However, Microsoft had tremendous resources buoyed by its extremely profitable software licensing. It leveraged this to develop a copy of both the Netscape web server and Sun Java, then tied both to Windows. The web aspirations of Netscape and Sun quickly faded, and Microsoft adopted their various advantages into its own offerings.

The difference today is that Apple’s iOS, macOS, watchOS and tvOS aren’t being broadsided by an innovative new voice-first paradigm that Amazon, Google and Microsoft freshly minted. Apple was developing Siri before its rivals even thought it was cool.

Apple’s Siri advantages

While Apple’s competitors have developed certain ideas that appear superior to Apple’s current Siri offerings (in services, hardware and third party connections), Apple also has voice-based strengths of its own. Apple leads globally in the breadth of languages Siri supports and understands.

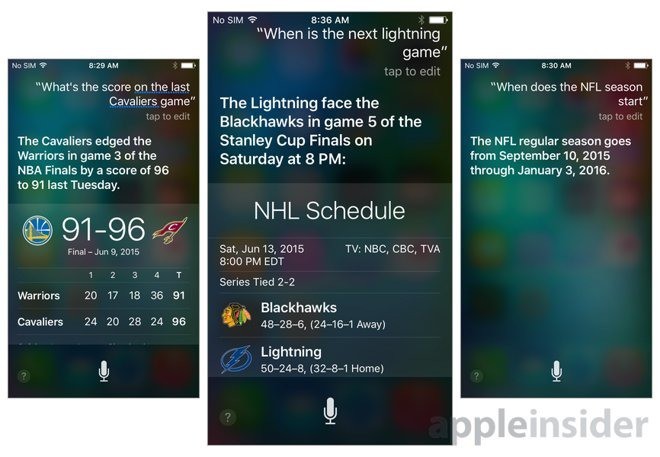

Siri also plays into Apple’s strength in accessibility, as well as the company’s efforts to lead in security and privacy. Siri also maintains a clear edge in the presentation of specific answers, notably sports scores and information on games, players and broadcasts.

Apple also worked to tie its HomeKit automation framework to Siri, enabling users to control lights, locks and other features with their voice before even releasing a touch-based interface in iOS 10’s Home app.

Apple’s Siri also has a far greater number of voice-based users than any other voice-interface rival. In fact, most of Amazon’s users also have access to Siri. So when iOS 10 introduced new Siri Domain expansions for third party voice features, both users and developers were already aware of the potential opportunity.

Further, Apple’s interlocking strategic developments means that developers building support for Siri Domains and Intents can also leverage the same work to build third party service extensions for Maps.

Moving from Alexa to Siri is not difficult. In contrast, moving from iOS devices and the rest of Apple’s platform to new hardware running a different ecosystem, just to access another voice assistant, is a much more difficult transition for users to make.

Apple is already doing what it needs to do

While rivals have copied Apple’s work with Siri, Apple has also been quick to adopt voice-first innovations that originated elsewhere, including always-listening features and beamforming with multiple microphones. It has also erased third party connections as an outside exclusive.

Siri has also made the jump from iPhones to Apple’s Macs (following Google and Microsoft bringing their voice services to PCs) and TV appliances (following Amazon’s lead in voice-based TV guidance). Apple also debuted Siri across both of the company’s wearable products as a key feature. In fact, there has even been some criticism that AirPods might require too much use of Siri.

In addition to expanding and entrenching where Siri can be used, Apple has also been working to improve the sophistication of Siri, particularly in its ability to remember expanded context (beyond current tasks like assigning yourself a name or saying how to pronounce names of your contacts) as well as its ability to work with third party apps and services.

Apple’s 2014 establishment of a corporate office and R&D center in Cambridge (below) and its 2015 acquisition of VocalIQ–a startup that originated with the University of Cambridge Dialogue Systems Group and focused upon automotive projects with carmakers including General Motors–show a clear investment in voice-first interfaces beyond simply following others.

A report from last November detailed job listings stating, “Apple is entering an exciting phase in Siri development, and we are aiming high both in terms of what Siri can do and the software engineering practices we follow in developing it. You will be working in a team of highly talented software engineers and speech scientists to expand the capabilities of Siri.”

That makes it a bit premature to assume that the barely profitable experiments in voice-first assistants conducted by Apple’s rivals are winning or leading in any meaningful way, although it does allow lazy journalists to generate sensational-sounding reports.

In 2017, Siri looks to be a key area of advancement at Apple.