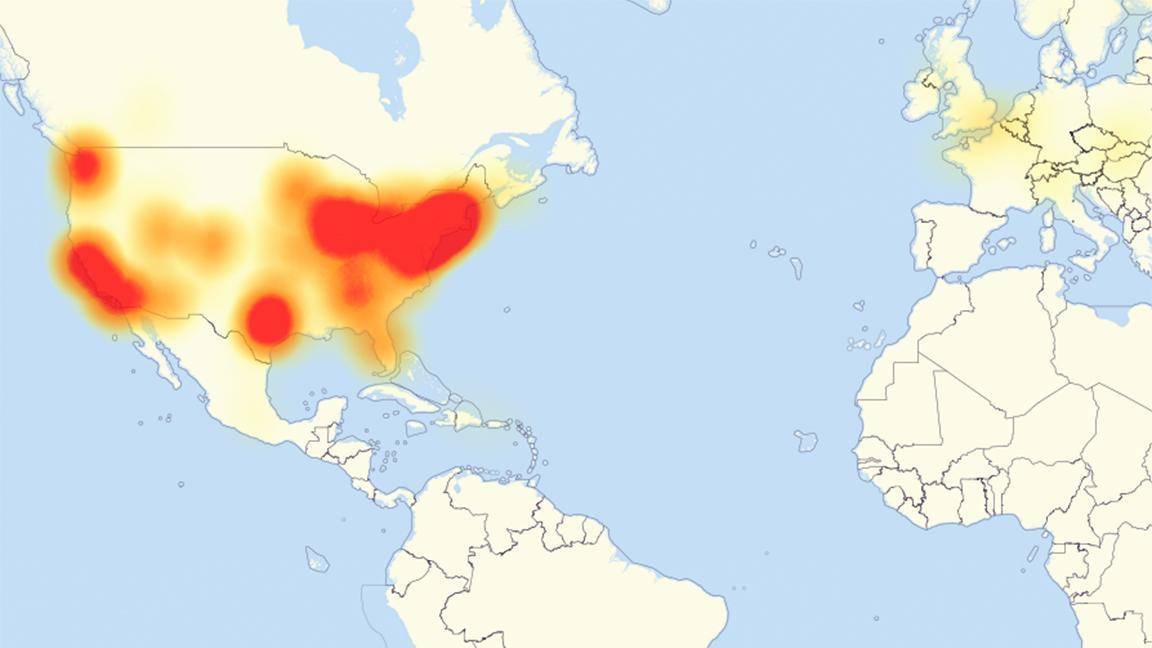

A map shows internet outages caused by the Oct. 21 DDoS attack. (Courtesy of DownDetector)

A map shows internet outages caused by the Oct. 21 DDoS attack. (Courtesy of DownDetector)

A massive cyberattack on Oct. 21 hit Dyn, a domain registration service provider, and temporarily shut down several major websites including Twitter, Netflix and Reddit.

Hackers used what’s called a distributed denial of service, or DDoS, to knock out the internet giants.

DDoS attacks are carried out when hackers infect several devices with malware that sends numerous requests to a targeted server or network. The flood of traffic can lead to a website slowing down or going offline completely.

Experts now believe the October DDoS attack was the largest of its kind ever discovered. The security firm Flashpoint released a report indicating it was the work of amateur, independent hackers instead of politically motivated state-sponsored actors. The hackers have not yet been conclusively identified, although a group called New World Hackers is claiming responsibility.

Dyn estimated the DDoS attack stemmed from up to 100,000 “malicious endpoints.” The perpetrators hacked into people’s Wi-Fi-connected devices, like web cameras, to launch the attack. These interconnected devices fall under the blanket known as the Internet of Things.

Joining us to discuss the recent hack and the danger DDoS attacks pose both on- and offline is Dr. Ray Klump, professor and chair of computer science at Lewis University in Romeoville and the director of its master of information security program.

Below, a Q&A with Klump.

![]()

Chicago Tonight: Were you surprised by the cyberattack on Oct. 21?

Ray Klump: Not entirely. I’m surprised by the devices that carried off the attack. Largely, it’s believed that the denial of service attack was caused by non-traditional computing devices.

Usually when there’s this denial of service-type of attack, your computer has been affected by some piece of malware that has turned it into this agent that is sending a bunch of traffic – a bunch of nonsense – to a server that’s being attacked.

So you’re flooding that server and you’re causing it to choke. It can’t distinguish between good traffic and bad traffic and it starts to reject you. That’s a denial of service. It’s a distributed denial of service because you’re enlisting all these computers – people’s computers, they don’t realize that this is going on – you’re enlisting this army of bots, basically, to go after a target.

In this situation, what appears to have happened is they weren’t using actual computers, but rather these computer-equipped connected devices, like security cameras and routers connected to the internet. So things without a keyboard, things we don’t consider computers that we use every day – these were the ones responsible for creating the traffic that flooded the servers and networks.

CT: How were they able to hack into Wi-Fi connected devices?

RK: This piece of malware takes control of the internet port on a device to tell it to send out traffic to such-and-such a location. The reason why this malware was able to do that, is because some of these pieces of equipment are equipped with services that have default passwords that are well-known, that have been published online, and nobody bothered to change them on these devices because no one thinks of them as computers, so they don’t bother to change the default passwords.

And in some cases, particularly with poorly-designed devices, they have no way of changing the default passwords. So the default password is known and there’s no way to change it. So that makes such devices extremely susceptible to this type of malware logging into a device and telling it to send this traffic to wherever it wants to go.

CT: Was the Oct. 21 attack really the largest DDoS attack ever?

RK: Yes. It’s the largest distributed denial of service attack s so far.

CT: What’s the impact of these attacks on users? Is there a risk of personal information being compromised?

RK: It’s not so much an issue of privacy. It’s an issue of functionality.

Let’s take it away from the perspective of our everyday internet usage and talk about it in terms of critical infrastructures.

For example, if a distributed denial of service attack is done against a piece of switchgear on the electrical grid – all of these are now interconnected through computer communications.

If a DDoS attack targets one of these switchgears or ComEd’s control room, then all of a sudden ComEd has no visibility into what’s going on in the system – their ability to see that there’s a lot of power flowing into a particular neighborhood. In that case, they’d better do something to reroute it or else something will get destroyed and cause mass outages. Their ability to see that decreases, so their responsiveness decreases, so it becomes a lot easier for someone to coordinate an attack on the electrical grid because the people responsible for operating it have no way of seeing what’s going on.

I think that’s a much more worrisome prospect of these DDoS attacks than our inability to get onto Amazon or Twitter. That’s the troublesome part about this. If the utility companies don’t have their act together and aren’t able to distinguish this type of traffic from legitimate traffic, then they can be attacked just like Twitter and Amazon the other day.

CT: At first it just seems like an inconvenient problem, but couldn’t it spiral into impacting emergency services?

RK: It certainly could spiral into that. Now it’s an inconvenience, but certainly, if it’s used to disrupt critical traffic that we depend on to keep the lights on, that’s a whole other problem.

CT: What can internet users do to protect themselves?

RK: If you have one of these devices, a security camera or router, it’s important to either throw them out and replace them with different ones or change the default password.

Let’s suppose it’s a more traditional DDoS attack where it’s targeting your computer with a keyboard. The easiest way for your computer to become one of these bots that ends up adding to this garbage traffic being sent to targeted servers is by clicking links in an email.

You’ve heard time and time again not to click on links that you see in emails, but people still do. They’re called phishing scams and people fall for them all the time. What happens is very subtlety, without people noticing, the malware gets on your machine and turns it into a remote-controlled agent of the DDoS attack. So, don’t click on those links or links on unfamiliar websites either because that just as easily can get malware onto your system.

CT: So these hackers aren’t using their own devices as a conduit for these attacks?

RK: They don’t have a readymade army so they’re taking your stuff and making it part of this army that they’re making on the fly.

CT: Can you notice when your device is being used?

RK: If done well, it’s not really apparent to you. It won’t necessarily make your system slow down and the amount of traffic that’s being pumped out of your machine and onto the network is probably going to be throttled to the point that it won’t slow down your internet connection much either. But certainly people can be obnoxious about it, and like a bull in a china shop, just flood your own network with the junk and then you’ll really notice something going on.

CT: What are the next steps in preventing DDoS attacks?

RK: I think it’s important for people not to think that it’s the entirety of this Internet of Things idea. The Internet of Things can be very useful to us. The problem is security is an afterthought when it comes to the design and implementation of some of these devices. The focus on security needs to baked into the entire design process or else we’re going to see more and more of this as additional devices of this type go online.

We need to go way beyond what we traditionally think of computers. Every device can’t have a Wi-Fi connection.

Think about our cars. When you get automatic-driving cars that get sensory information from the road and traffic signals – if it a denial of service is done on those, it could be awful. Security needs to be a constant focus in the design of all these devices. That’s why this is such a pressing problem. There aren’t people who understand that – or understand security and software development.

We need take a little bit of a pause to make sure we come up with standards – testing standards to verify that all these devices are not the type that can be hacked.

Follow Evan Garcia on Twitter: @EvanRGarcia

Related stories:

Dialing Up Defenses to Cybersecurity

Dialing Up Defenses to Cybersecurity

Sept. 15: Whether fictional or real, stories of hacking appear to be everywhere. We discuss online security and the public’s fascination with hackers with two local experts.

Assessing the Risk, Damage After Illinois’ Voter Rolls Hacked

Assessing the Risk, Damage After Illinois’ Voter Rolls Hacked

Sept. 6: The State Board of Elections computer hack may have been smaller than first thought. Now it seems the personal information of only 90,000 Illinois voters was compromised. How safe is voter information? We get the latest.

Ted Koppel on America’s Vulnerable Power Grid in ‘Lights Out’

Ted Koppel on America’s Vulnerable Power Grid in ‘Lights Out’

Nov. 9, 2015: The veteran journalist discusses his new book about the risk of cyberattack facing the power grid in the United States and the inadequate measures being taken to protect it.

![]() Dispelling the Myths of Email Privacy, Security

Dispelling the Myths of Email Privacy, Security

Oct. 12, 2015: A discussion about the misconceptions and myths of email with Jeffrey Cramer, a former federal prosecutor who now heads the Chicago office of security firm Kroll.