Photo:

iStockphoto/Getty Images

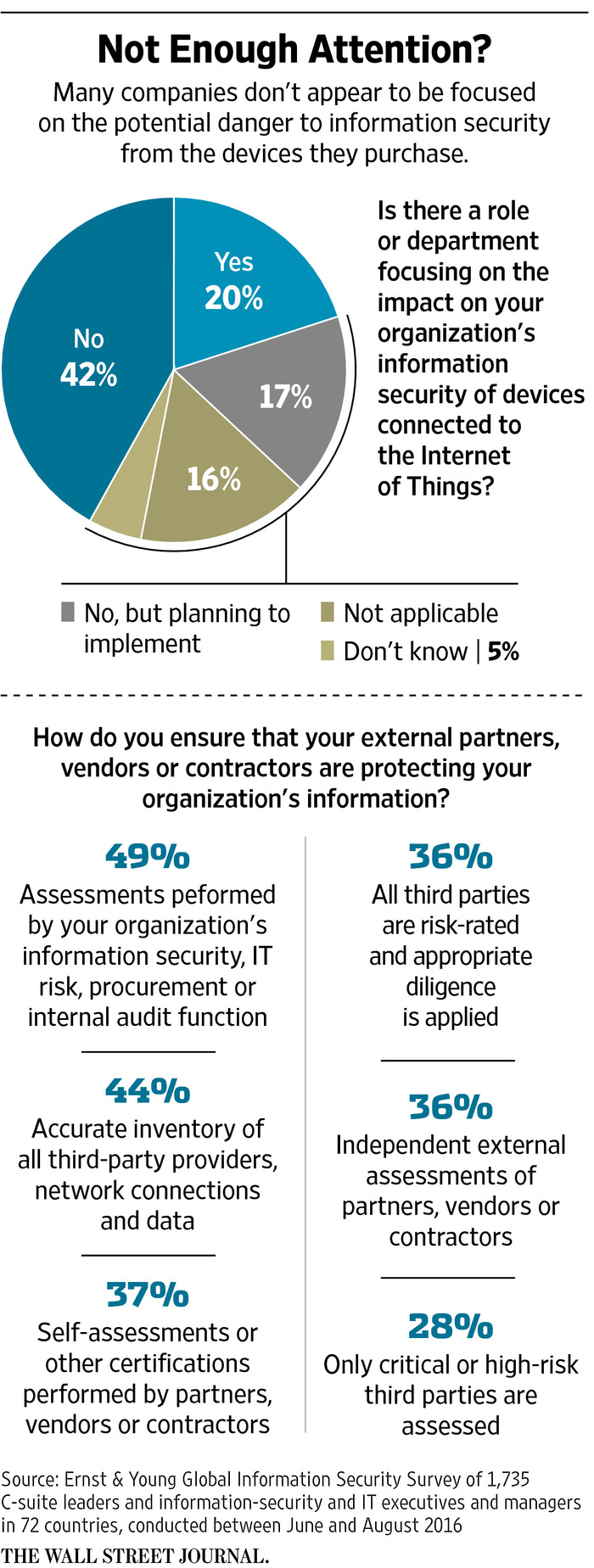

Companies are expected to spend more than $3 trillion on workplace technology this year, buying everything from traditional servers to augmented-reality glasses. For many, those purchases will make them more efficient, more innovative—and more vulnerable to attacks on their information security.

That’s because when they consider which new technology to buy, companies often base their decisions largely on such factors as cost, reliability and deployment concerns. But, in my experience as an adviser to companies on information security, and in my academic research on security issues, I’ve seen that companies often don’t give enough weight to the most important factor of all: How secure is that device or service? And I’ve seen them pay the price for that.

Companies need to understand from the start that their information is only as safe as their most vulnerable piece of workplace technology. And the growth of the Internet of Things will only exacerbate the security risks.

First, many people think of most devices in the Internet of Things as harmless gadgets, and push for their company to adopt the newest, coolest devices, even when the gadget’s internet connectivity adds questionable value—think of the “smart” toasters and internet-connected coffee machines that can be found in many break rooms. Any gratuitous internet-connected device increases the size of the target painted on a company.

Journal Report

- Insights from The Experts

- Read more at WSJ.com/LeadershipReport

More in Workplace Technology

Also, to keep down the costs of production, companies that make devices that are part of the Internet of Things—frequently startups operating on a shoestring budget—often skimp on security.

So, what does a security-first approach to workplace technology purchases look like? Following are some basic steps that companies that are smart about security take when purchasing new workplace technology.

Do your technology reputation homework. Companies need to independently research the security history of the product or service they’re considering, and the vendor’s history.

The information is out there if you look for it, so companies can’t let themselves be caught unaware: Has the technology press highlighted repeatedly unpatched, severe flaws in the vendor’s products? Is the internet full of long threads of security researchers complaining about the company’s refusal to fix vulnerabilities?

A vendor’s own history of breaches is important, too. Companies shouldn’t trust their sensitive information to technologies that were built by vendors with a reputation for failing to defend their own assets. If a vendor has a history of security breaches, were they due to targeted, sophisticated attacks that were unforeseeable, or were they due to careless errors and failures of management?

Ask good questions about security testing. Companies should never trust their business and its information to technologies that haven’t been rigorously audited for security flaws. They should ask the vendor which security consultancy does its external code auditing and product testing, and ask to see the auditor’s reports for the products they’re considering. If the vendor is unwilling to share the reports, companies should insist that purchase contracts contain promises about the quality and frequency of the vendor’s security testing.

Some additional questions to ask: What types of internal processes does the vendor have for security testing before a product ships? Does the security team have the power to stop the shipment of a product for security reasons?

Previously in Technology

- Why Digital Transformations Are Hard

- Baidu’s Andrew Ng and Singularity’s Neil Jacobstein: This Time the AI Hype Is Real

- How Augmented-Reality Glasses Work for Business

- Ten Rules of Etiquette for Videoconferencing

- Wearables in the Workplace Bring Legal Concerns

- The Key to Getting Workers to Stop Wasting Time Online

Find out what happens after the purchase. Some vendors are great at building shiny, new technologies quickly, but later they’re unreliable about fixing the mistakes in their code when it’s shown to have severe security flaws.

Companies need to ask about the level of detail in a vendor’s security advisories—the notices that technology providers issue whenever a new vulnerability is discovered in their products: Are the advisories detailed enough to allow customers to meaningfully mitigate the risks that the new vulnerability has caused to their systems?

Other questions to ask are how long it takes vendors to patch vulnerabilities, how long vendors plan to support the products the company may buy, and whether the vendor solicits help from the public with finding security flaws.

A broader question to ask is: Does the company promise to follow best business practices for fixing faulty code in line with industry standards?

But it’s not enough to ask all those questions. A company should have the vendor’s answers written into the purchase contract as promises.

And finally, the company should find out whether the vendor has ever threatened to sue one of its own customers or a security researcher for reporting a security problem. If the answer is yes, the company should run away as fast as it can. Although vendors may deny making these types of threats, news of this kind of behavior tends to make its way onto the internet, so it can be found. And to determine whether a vendor has ever actually sued, or been sued by, a customer, a company can search legal databases.

Trust but verify. Even products with the highest quality of engineering will inevitably suffer from security vulnerabilities. Although responsible technology vendors will let customers know as soon as possible when a vulnerability in their products puts customers at risk, it’s always a good idea for companies to keep track of their vulnerabilities for themselves as much as possible.

So, when making a purchase, companies should ask vendors for an itemized list of all the third-party components and code in their products and include the list in the purchase contract. That allows the buyer to monitor vulnerability databases to see if any problems are reported with anything on the list, and to double-check the vendor’s speed in issuing security advisories on widely known new problems.

Dr. Matwyshyn is a professor of law and of computer science at Northeastern University. She can be reached at [email protected].

0 COMMENTS