Bankers inclined to scoff about robo-advisors and the willingness of the typical consumer to put their financial eggs in such baskets had better examine their own purchasing habits.

How often have you taken the recommendation of Amazon to add a particular book, tool, food, or other item to your order when you didn’t visit the site intending to buy it?

When you Google something, how often have you gone beyond the first screen of search results—the first screen being Google’s algorithmic guide to what best fits your need?

Recent research by Accenture indicates that consumers worldwide have more affinity for robo-advice and potentially doing business with the “Bank of GAFA”—Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple—than should allow bankers to sleep at night.

In fact, it is quite possible that some of them, in the wake of ethical banking lapses, may trust the robots more—in spite of the fact that humans program them.

Acceptance for automated advice growing

Accenture’s January 2017 Global Distribution & Marketing Consumer Study, based on an international survey of 33,000 consumers in 18 countries, found that 71% are open to computer-generated advice to help them determine which bank account to open. (Specifically, respondents were saying that they would use advice generated entirely by software.)

And nearly one in three—31%—would switch to Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, a supermarket, or a retailer for banking services.

Source: Accenture 2017 Global Distribution & Marketing Consumer Study. Click on the image for a larger version.

For 18-to-21-year olds, 41% would be willing to switch to a “GAFA.” Accenture sees this as an indication that younger consumers still see some value in traditional financial institutions.

These results aren’t confined merely to banking, but apply to other financial services as well. The same survey found that 74% of those sampled would use computer-based advice for buying insurance and that even more—78%—would use robo-advisory service for investment decisions. “GAFA” service would be acceptable to 29% of the sample for insurance shopping and 38% for investment advice.

Varying results were seen depending on the consumers’ home country, with Americans generally displaying high willingness to accept fully automated service—but not the highest rates, by far.

In willingness to use robo-advice for banking, the top five nations were, in descending order: Indonesia (90%); Thailand (87%); Brazil (84%); Chile (82%); and Singapore (80%). U.S. consumers were the ninth-largest national group to willingly accept automated banking advice, at 72%. Interestingly, Canadians were less willing to deal with banker-bots, with only 69% favoring the service. (The percentages represent the sum of those who were somewhat willing and very willing.)

U.S. consumers came in eighth (74%), in terms of accepting computer aid for an insurance purchase, and seventh for investment advice (79%).

More broadly, respondents were also asked if they would accept advice on retirement planning wholly from a computer. There the U.S. ranked eighth (68%).

Accenture analysts point out that the countries with the greatest acceptance, even enthusiasm, for robo-advice are emerging economies that have substantially short-circuited the traditional path of financial services development. Accenture points out that in those markets smartphones and other digital devices tend to be the main vehicle for handling financial services.

Why so much acceptance of robots?

Somewhere between the sinister old science fiction world of threatening, life-controlling computers and robots and the advent of Apple’s Siri, Amazon’s Alexa, and BofA’s Erica, people’s attitude towards having major aspects of their financial existence run by computers, or at least, advised by computers, has evolved dramatically. If anything, a preference for the machine appears to be emerging.

“People are starting to try this out in low-risk areas,” says Stephanie Sadowski, managing director at Accenture. “And once people have had success with these types of services, interest can grow really high.” Sadowski is North American lead for Accenture Distribution and Agency Management.

In some ways, Sadowski says, people appear to be developing a greater trust in software-driven advice than in human advice. But if a customer distrusts a human representing a financial organization, why would they, if they thought things through, trust a computer program written by a human?

Sadowski has a ready answer for that: machine learning. As software programs increasingly incorporate artificial intelligence, she explains, the “machine” takes over its own direction. It learns what works and doesn’t work with consumers and better adapts to a customer’s preferences. The idea is that it is relatively untouched by human hands.

Sadowski says machine learning is what has made Amazon’s customized interface so successful.

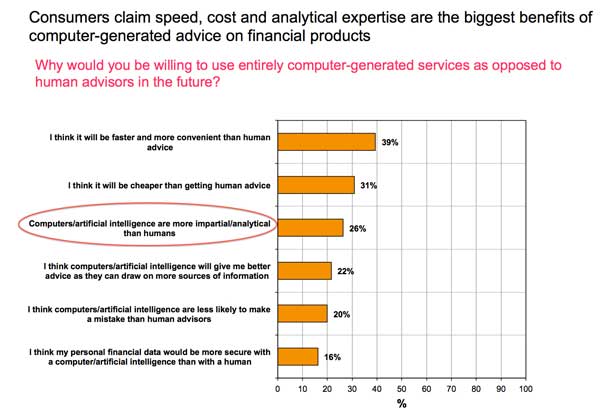

As the chart below shows, consumers seem to “get” this at some level. These results from the worldwide sampling track with U.S. findings. While the top two bars reflect a desire for speed and a desire to hold prices down, the fact that the third-ranking factor is “Computers/artificial intelligence are more impartial/analytical than humans” is intriguing.

Source: Accenture 2017 Global Distribution & Marketing Consumer Study. Click on the image for a larger version.

Faster responses, and going right to the answers they want, seem to be consumers’ preferences here.

But that’s not the entire picture…

When only a human will do

Many of the countries whose consumers had an even stronger attraction to computer-based advice in the banking area are in Europe and Asia and reflect those financial mindsets. Sadowski pointed out that branches have long been less numerous in those markets, versus the U.S., which gives those financial players offering robo-advisory services a leg up. However, even in those markets customers sometimes want to be able to see a human being for service.

“So, there still needs to be a physical footprint,” says Sadowski, to accommodate that desire.

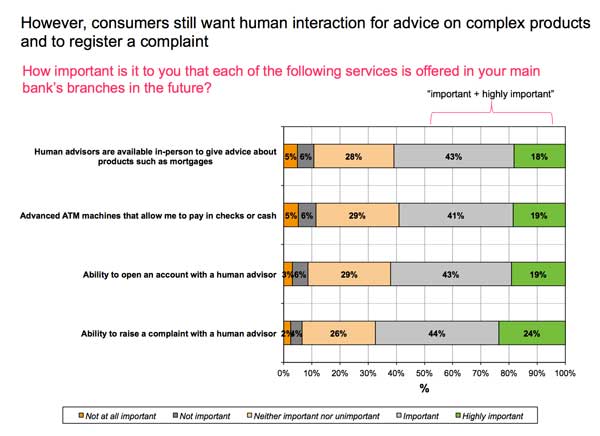

Source: Accenture 2017 Global Distribution & Marketing Consumer Study. Click on the image for a larger version.

Complex purchases create the demand for continued human interaction in physical offices, suggests Sadowski, as shown in the top bar of the chart above. There are other reasons, however. A notable one is reflected in the bottom bar, where respondents worldwide rated it important (44%) or highly important (24%), for a total of 68%, that they have the ability to raise a complaint with a human advisor.

Interestingly, this varied by country. For example, this was important and highly important to 78% of Americans—and 80% of Canadians—while only to 34% of Japanese consumers.

What this means for retail banking

Sadowski suggests that increasing comfort with robo services and willingness to do business with atypical providers puts a new spin not only on branches but also on other human contact points such as call centers.

“You are going to need people who are problem solvers, not product sales experts,” Sadowski explains. This means banks will have to hire for such skills for those places where people help people in the bank. Being good at listening and at working out resolutions will become more important for new hires than will the ability to sell a checking account.

Sadowski says some banks already seem to understand the change that’s underway. They have been working to “pivot” their thinking, she says.

Institutions that fail to master this pivot, she adds, face not necessary extinction, but near-irrelevance.

Already, Sadowski points out, banks run the risk of being the operators of the financial system’s rails and stations, and little else. Nonbank digital players require banking services and access to the payments system, but the industry faces the risk of becoming a bunch of “dumb vaults” and “dumb pipes,” according to Sadowski.

“Ultimately, banks have to find ways to embrace fintech,” says Sadowski. She warns that as the “GAFAs” of the economy turn more attention to financial services, banks will find them to be extremely disruptive.